Insights

Jan 29, 2026

Was your 2025 success a low-probability outcome in a high-risk year?

Jamie Rodney

It’s the end of January. Renewals are done, portfolio roll-up is complete.

2025 market performance was strong. The discussion moves to whether the risk view and outlook for 2026 justifies the relief everyone is probably feeling, especially when the risk view doesn’t know it’s now 2026…

Now everyone's asking you: rates went down, are we managing risk to where we’ve been or where we’re going?

Physically, 2025 delivered something extraordinary. Four out of five hurricanes reached major strength. Three intensified to Cat 5, only the second time in history that the North Atlantic has produced more than two Cat 5s in a single season (2005). Melissa devastated Jamaica beyond anything previously observed.

The market response? Strong performance, rates softening and capital flowing in.

With increased wildfire and severe weather losses, the strong 2025 conditional performance was driven by no storm making it to the US coastline and impacting a large exposure. How likely or unlikely was this scenario?

Thinking about this probabilistically: If 2025 played out a thousand times with identical climate conditions, the same ocean temperatures and the same atmospheric patterns, how many scenarios produce zero US landfalls? Maybe 100. Maybe 200. Maybe 500?

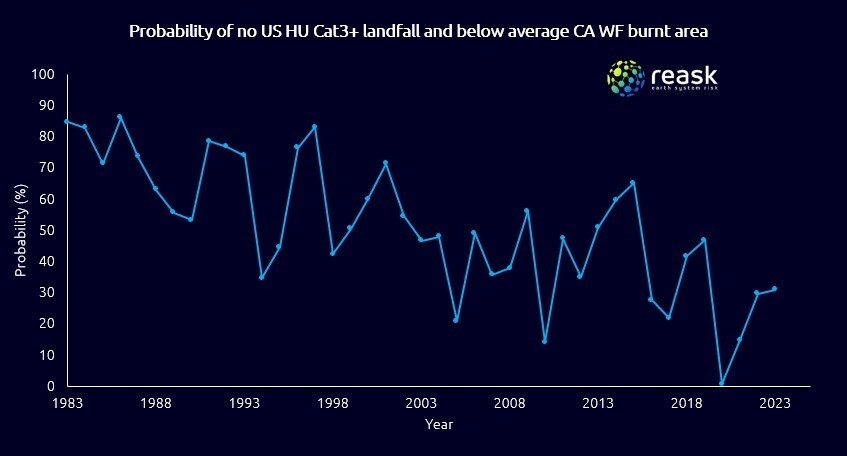

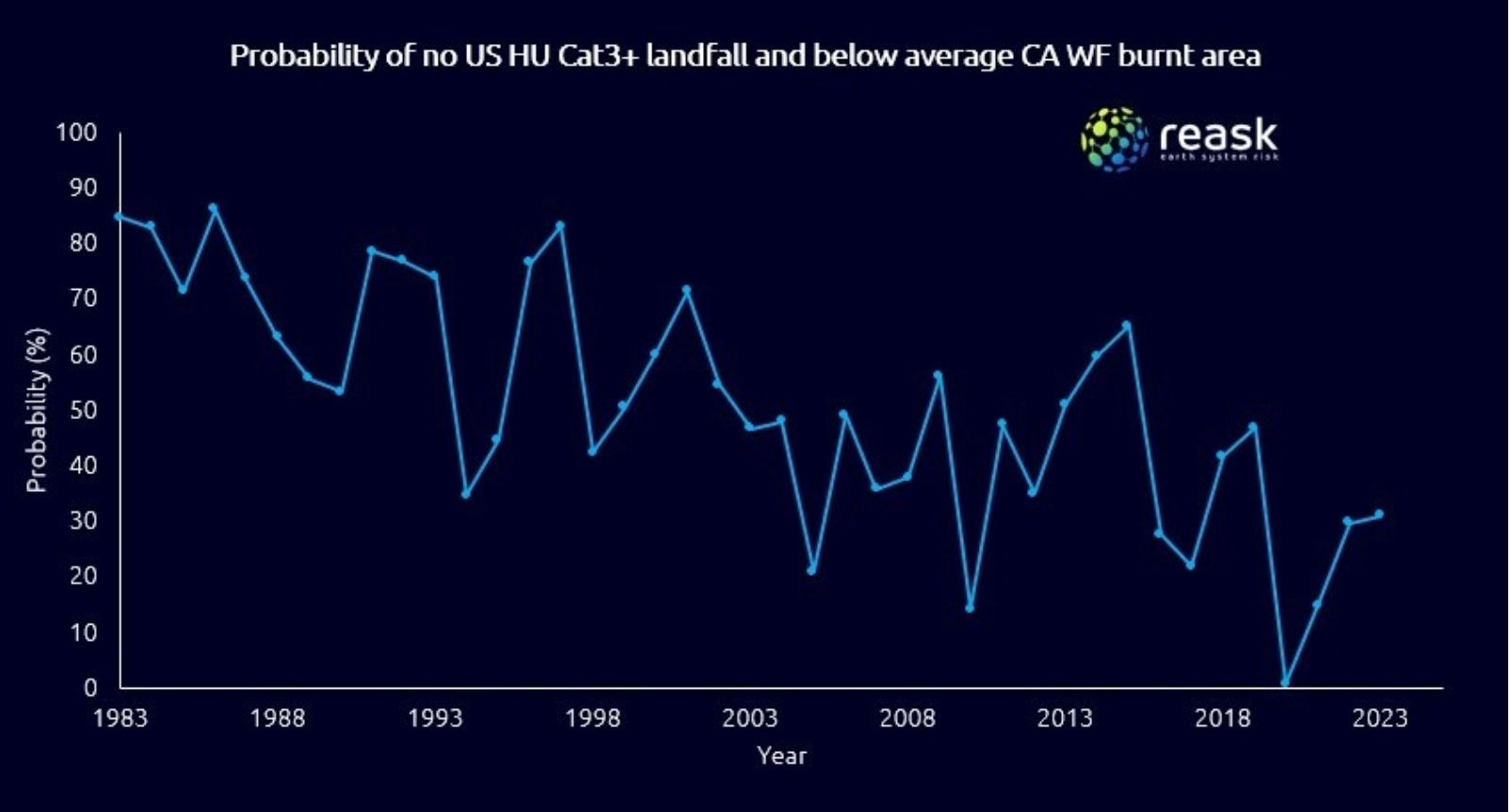

Was your 2025 "success" a low-probability outcome in a high-risk year? The probabilities of favourable conditions for strong performance are becoming more uncertain relative to what we have observed in the historical record (Figure 1).

But the sea surface temperatures that drove 2025 intensification rates? They're not going away. The physics hasn't changed just because rates went down.

Figure 1: Reask probability of no US Cat 3+ landfalling hurricanes and low California wildfire activity (measured as area burned). Reask models conditional on climate automatically capturing the correlation between events and climate conditions to assess the most favourable conditions for performance across hurricanes and wildfires.

You need to start somewhere

So, you tried to account for this change in the climate. "Increase hurricane frequencies by 20%."

Why 20%? And not 15, 40, or 70%? This feels somewhat arbitrary, especially given the lack of data to credibly benchmark using the historical record.

You don’t know the real answer. Your gut tells you that adjusting down doesn’t feel right given what you’re seeing in the climate. You want to add some level of conservatism to the model to account for this uncertainty but don’t want to introduce a step change, so you went with 20%.

But Florida and New York aren't experiencing identical climate responses. Gulf Coast and Northeast exposures face fundamentally different atmospheric conditions.

A 20% frequency adjustment treats them the same.

Now you wonder: What did my adjustment actually account for, and is it grounded in real physical outcomes?

Looking back and looking forward at the same time

An underwriter pushes back: "There's never been a major Northeast event. Your model's too high."

They're not wrong about history. 2006-2016 saw no major US landfalls. A decade of relative quiet with low losses, strong returns and abundant capital.

Then a series of events: Harvey, Irma, Maria, Michael, Ida, Ian, Milton…

And in 2025, three Cat 5s with intensification rates your models weren't accurately calibrated to capture.

History told one story and the physics wrote another. The gap between them is the risk you’re running.

When the next event or series of events hit, and they will, someone asks: "Was this captured in your model? What was the return period?"

When you work in risk, you accept that uncertainty is unavoidable. It grates constantly against the idea of a single “best estimate,” because the risk world refuses to resolve cleanly into one number.

This tension is the foundation of (re)insurance.

But uncertainty has a dangerous property: when the uncertain thing actually happens, small modelling assumptions don’t stay small. They compound. Errors that were tolerable in expectation become amplified in reality. And at the scale reinsurance operates, that amplification can be existential to the business.

Business and careers don’t end because a model was imperfect. They end because the business took on risk it didn’t understand or thought it did.

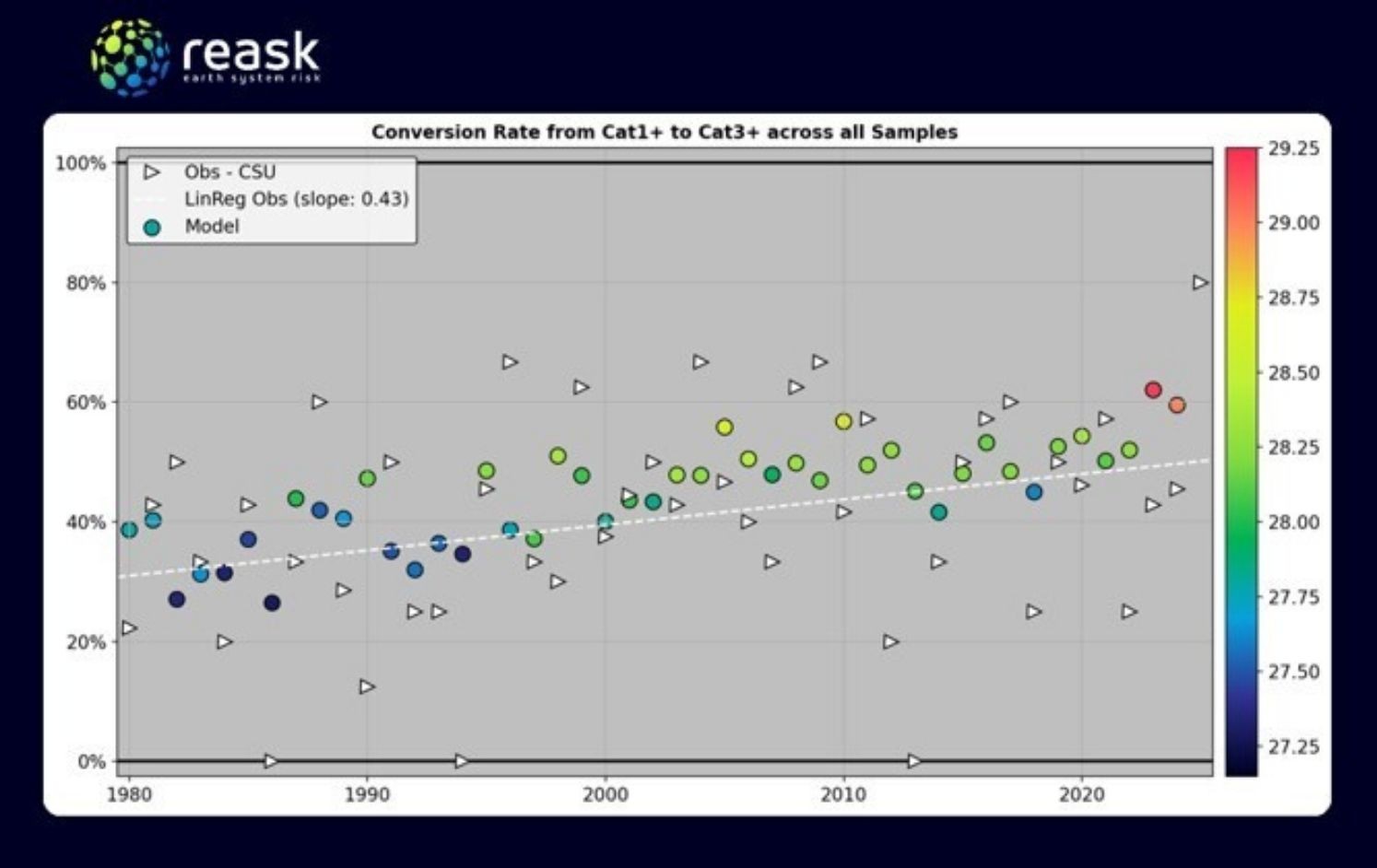

Figure 2: North Atlantic Hurricane conversion rates as a function of Sea Surface Temperatures. More hurricanes are converting to major strength as the Sea Surface Temperature warms.

Your position

You're caught between three constraints:

You can't abandon legacy models. They're embedded into critical processes.

You can't ignore the climate signal. Ocean temperatures are too far outside historical norms. Recent events align too well with thermodynamic expectations. More hurricanes are converting to major hurricanes (Figure 2).

You can't just rely on generic adjustments. Basin-wide percentages or statistical landfall adjustments typically miss regional specificity. They don't explain why, for example, Florida and the Northeast face different risk trajectories and uncertainty. They don't give you a physically defensible story.

You sit between trying to acknowledge physics without destroying infrastructure and staying defensible without being overly conservative and impacting commercial viability.

And as the climate changes, the gap between "what the model says" and "what the climate suggests" widens.

The intensification rates we’ve seen aren't random fluctuations. They're consistent with high ocean temperatures and atmospheric conditions fundamentally different from typical model calibration period.

Over the next cycle, will your 2025 performance look like a dangerous missed signal or sound underwriting?

The climate isn't standing still. Can your risk view be honest about benchmarking performance?

Renewals happen every year, it’s the one probability we can predict with certainty. The risk is letting the one that exposes a mistake be the one you weren’t ready for.

Next post: Reask’s approach to solving this. If you can’t wait, message me or a member of the Reask team.

Stay in the loop

Sign up for the Reask newsletter for the latest climate science, model updates, and industry insights